The Life of Meanings turns the common phrase “the meaning of life” on its head. As opposed to thinking of life as a long and winding narrative, it could be better understood as an amalgamation of countless moments, memories, symbols, and anecdotes scattered in loosely chronological order. The way we replay our past varies by individual—it depends on what we choose to remember and what we consciously bury in order to forget. The rest could be considered out of our control. Carlos Estévez’s practice digs into the collective consciousness by diving into a deeply personal dreamscape and asking the viewer to look closer at themselves. By reflecting on his dreams, past experiences, and the knowledge that comes with being a voracious reader, Estévez creates an entire world within one work, giving the viewer the opportunity to place their own interpretations and reflections onto its rich and intricately detailed surface. In an attempt to better understand and explore Estévez’s overall practice, and for the purposes of this essay, the works presented in The Life of Meanings will be contextualized through a Surrealist lens—evoking the concepts of dreams, self-reflection, the subversion of found objects, and automatism. Surrealism is nearly synonymous with the concept of dreams, making Estévez’s practice a unique continuation of an incredibly rich history of artists who used dreams and dream-objects as a way to explore their subconscious and share those ideas with the viewer.

Estévez is perhaps best known for drawings and two-dimensional sculptural assemblages that feature marionette-like figures. A typical work by Estévez recalls the moodiness and obscurity of Surrealism, yet is rendered in a precise style reminiscent of architectural designs or technical, scientific imagery, particularly pre-modern medical illustrations, astrological maps, and alchemical charts and diagrams. The primary source of Estévez’s work is the human condition. He compares his process to be similar to that of alchemists—searching for ways to make gold but stumbling upon knowledge instead. Estévez’s works are deeply personal—reflecting on experiences, books he has read, and images he has seen in order to produce his highly detailed works. Estévez’s practice is, in my ways, a continuation of André Breton’s fascination with dreams, the unconscious mind, and how those dreams were interpreted and understood through the creation of dream-objects.

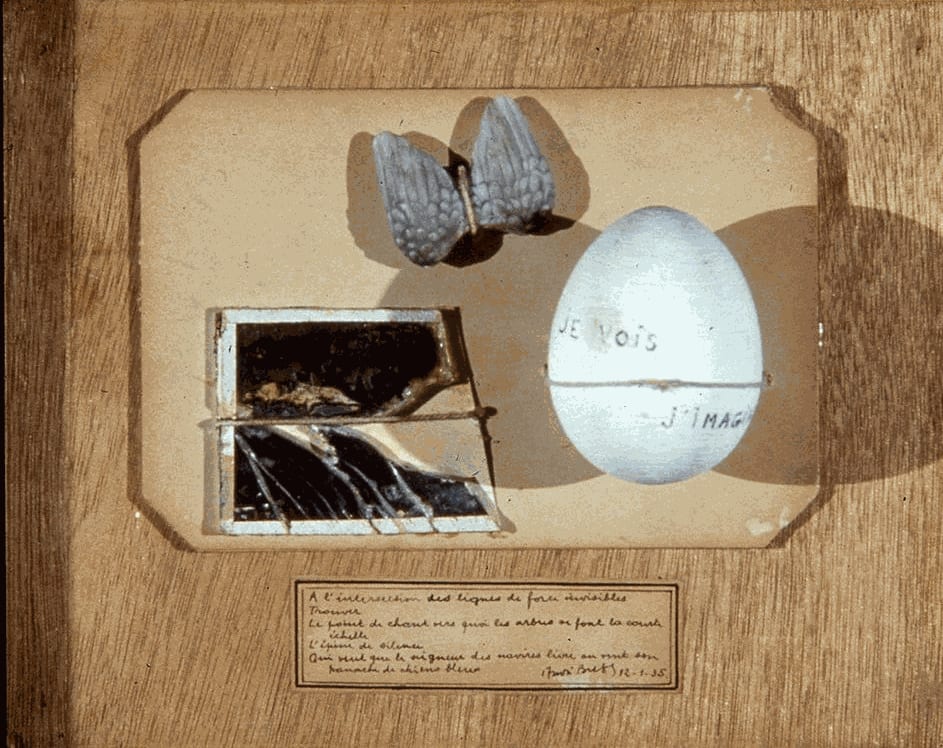

ANDRÉ BRETON. Objet à fonctionnement symbolique, 1931. Assemblage, bois, 24,5 × 41,5 × 32 cm. Photo: Philippe Migeat/Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Adagp, Paris 2021.

Our Marginal Waking Life in this Immeasurable Universe

Tarot cósmico (2022) represents humankind’s waking life. Life itself, represented by this interactive installation, begins with us at its center, hence the mirror that draws you in and invites you to activate the artwork. Each circular element represents an element of our lives. Surrounding the mirror is a ring representing the human body and its connections to the outer world. The ring that follows represents nature, and the following, elements of daily life represented by recognizable symbols. Lastly, the cosmic and planetary world looms over all of the other rings, reminding us of our connectedness to the universe and our marginal place within it.

The reference to tarot cards is significant as well, given that, historically, tarot cards were merely a pack of playing cards used from as far back as the mid-15th century in various parts of Europe. Today, reading tarot cards is a form of cartomancy, whereby practitioners use tarot cards purportedly to gain insight into the past, present, or future. Tarot cósmico is an interactive work that comes alive as the viewers begin to reflect on their own life and how these images relate to their own experiences. Created at the height of the pandemic, Tarot cósmico represents a moment of deeply personal and intellectual reflection on Estévez’s part, making this a work where the viewer is in direct conversation with the artist through symbols and imagery universally recognized. The work and all of its elements offer the viewer the opportunity to also, though not literally, gain insight into the past, present, and future.

The Uncanny, Unsustainable, yet Imaginable Cityscape

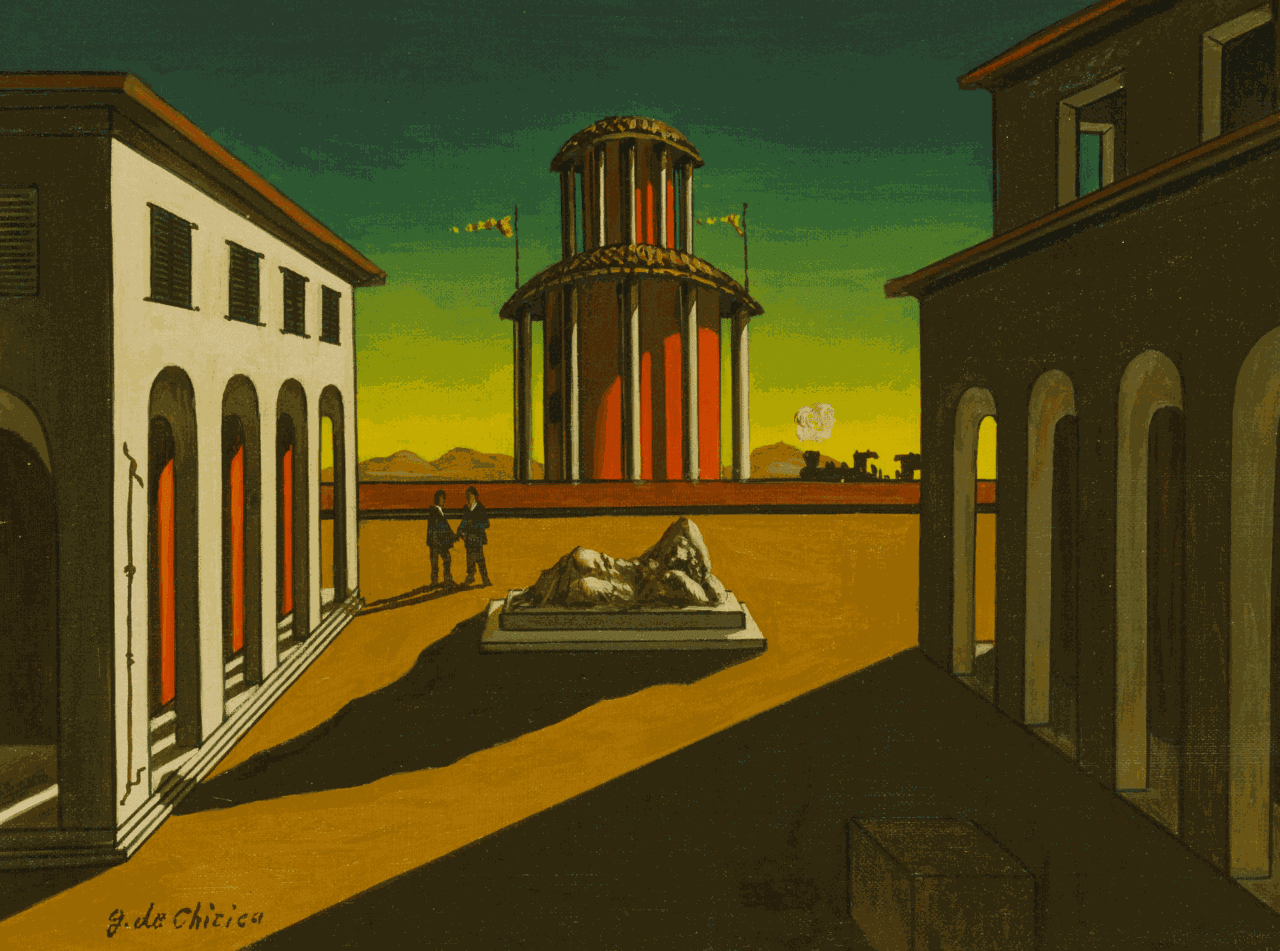

A major influence in the creation of objects within the Surrealist movement was, ironically, a painter. Giorgio di Chirico’s images hardly evoke any sense of clarity or reality. There is a sense of the uncanny, of something strange, something looming, and this is what made Chirico’s work such a central influence within the movement, and of particular interest to Breton. Chirico’s paintings depict an uncanny cityscape, with inexplicable objects as their focus. Estévez’s paintings included in The Life of Meanings also reference the city, and more specifically, the inner workings that keep a city alive. The painting’s inevitable stillness makes the entire city look as though it is in pause, perhaps resting, from the output required of maintaining everyday life. This is notable in Ciudad entropía (2022), where the influences of architectural plans and blueprints are visible in the depiction of the city. From afar, this painting looks entirely abstract, consisting of geometric elements that create a sort of buzzing sensation. Though the city appears frozen without any obviously visible movement, the viewer can envision the busy bees keeping the gardens trim, the roads clear, and the businesses opening their doors. There is also a hint within the painting’s title—entropy referring to a gradual decline into disorder. Given that the paintings appear orderly with the details stenciled in an incredibly clean manner, there is no denying that the title makes one wonder whether or not the city’s clean lines and courtyards can remain so within an unsustainable system. Unlike Estévez’s previous paintings, there is no figure included. In a sense, the figure could be missing for many reasons, but ultimately, he leaves that to you.

GIORGO DE CHIRICO. Piazza D’Italia, 1955. Oil on canvas, 11.75 × 15.75 in .

The Surrealist Dream-Object, Cabinets of Curiosities, and Unusual Connections

The stencils used in the first painting were subsequently used on the others. The similarity in some of the shapes and the reason as to why that is, is part of a much larger narrative close to the artist’s heart and heritage. Estévez refers to recycled and subverted found materials throughout his practice, while also making a statement about how the use of found materials is something he considers cultural. There are many references to scarcity within his work, reflecting on the fact that nothing goes to waste in Cuba—every item finding a new purpose in order to make life just a little bit easier. Cuban artists have long addressed themes specific to the island, to scarcity, to subversion of materials, and the unsustainable—Estevez’s practice is an extension of a conversation that has been ongoing within the history of art for decades.

ANDRÉ BRETON. Je vois j’imagine, 1935. Collage of object and inscribed poem on card on wood, 16,3 × 20,7 cm. ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London, 2015.

Though the paintings and their use of the recycled stencils certainly reference his interest in sustainability, the boxed assemblages not only reference the subversion of the found object, but also let us dive back in time to when Surrealists were interested in dream-objects and cabinets of curiosities. Though Surrealism was littered with many types of “objects” (poem-objects, dream-objects, found objects), it is clear that for Estévez, the dream-object had the most impact on his work. The Encounter of the Souls (2021) is a boxed assemblage made entirely of found materials and at the very top, inside the small cabinets, are notebooks that include the artist’s dreams written in as much detail as he could remember upon waking. Breton’s emphasis on dreams was directly linked to the creation of artworks and in this particular work, Estévez picks up where the Surrealists left off, incorporating dreams into the artist’s practice in order to achieve a better understanding of their subconscious. The Encounter of the Souls includes dozens of cubbies closed off by a small door labeled with a word or phrase. All of the objects inside the cubbies are found objects that have some sort of relation to the word on its respective door. For example, the door labeled “wisdom” contains a small antique flat iron. The viewer is encouraged to create a narrative or apply a personal interpretation to each set. When it comes to the antique flat iron and the word “wisdom,” one cannot help but think he is referencing to the wisdom of the artists who came before him. One of Man Ray’s most iconic readymade objects is Gift (1921), an antique flat iron with fourteen thumbtacks glued to its sole.

MAN RAY. Gift, 1958 (Replica of 1921 original). Painted flatiron and tacks Collection of MoMA. James Thrall Soby Fund, Image Copyright 2022 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

The cubbies are also a reference to one of art history’s quirkiest collecting practices, the wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities. Oftentimes, the word “cabinet” referred to a room and not necessarily a piece of furniture, but Estévez subverts the term, and creates actual cabinets that inside hold eclectic, rare, and remarkable objects—just as the art historical cabinets of curiosities did. The cubbies are in direct conversation with a figure that is covered in Daguerreotypes, which was the first publicly available photographic process and widely used in the 1840s. According to some, Photography threatened to exterminate painting. Instead, Photography forced painting into a different realm, and the Impressionist movement and painting en plein air was born. The Encounter of the Souls is a boxed assemblage that makes reference to the rich art history that brought us to where we are today. Estévez’s simpler boxed constructions, such as Los recuerdos del tiempo de vida (2018) share a striking resemblance to Joseph Cornell’s boxed constructions of the mid-1900s. Their enclosed surface allows the visitor to quite literally peek inside the artist’s mind and artistic reflections. It is only appropriate that Estévez includes two-dimensional collages in direct conversation with his boxed constructions, since, art historically; one could argue that the collage was the flat precursor to the many forms of the Surrealist object.

The “inveterate dreamer,” as Breton describes man in the first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), is far too concerned with his waking life, and does not pay nearly enough attention to his dream life. The Life of Meanings dives into the dreamscape—many of the artworks a direct result of Estévez’s interest in his own dreams, the interpretation of subconscious thought, his art making practice in relation to Surrealist theory, and the subversion of the found object to that of a dream object. The Life of Meanings is a continuation of one of art history’s most fascinating conversations through the mind and heart of an artist keen on contributing to it.